Every math teacher has heard this question countless times. Personally, when I hear this question from a student, my pulse quickens and my eyes surely suggest the enthusiasm for the impending discussion. Needless to say, I'm a little passionate about this topic and, hopefully, my view is fresh, unique, and helpful. This has not always been the case. At one time, my response was, at best, defensive and, at worst, insensitive. A thoughtful response should consider two things: (1) the student may be frustrated and (2) the student may be genuinely curious.

1. The student may be frustrated

This component to my answer to "when will we ever use this?" has developed more recently. Sometimes, a student may genuinely want to know what some practical uses are; most often, however, the question is really an expression of something like the following:

In this instance, we could respond initially by asking, "Is there something you don't understand?" This will usually lead to a discussion about the particular concept. This makes perfect sense. When students succeed at and enjoy a topic that is not overtly pragmatic (such as creating spiro-doodles) they seldom ask "When will we ever use this?" Students are not ultimately concerned about the application. Rather, they are interested in feeling confident, capable, and curious.

2. The student may be genuinely curious

All too often, the answer given involves money, recipes, carpentry or sometimes bridge building. Civil engineering notwithstanding, most instances cited above involve only computation (what many would call "numeracy") and fail to answer the need for the learning of higher math. Those of us with experience in engineering know that we did not need to compute a derivative or integral but, rather, we used software for computations and we needed to determine the parameters/variables in the problem as well as interpret/apply the results.

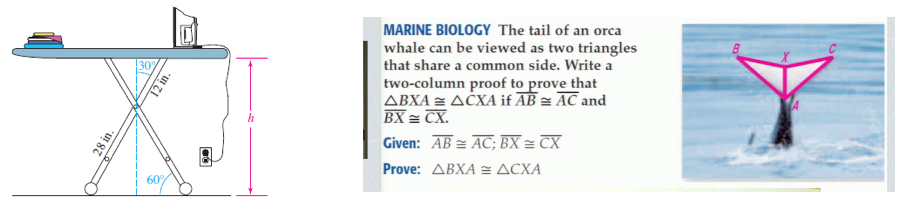

Too often, our answers remind me of the " Ironing Board" problem. In many Algebra or Geometry books there lurks a problem in the exercises with a diagram of an ironing board along with some given parameters and the student is asked to find the measure of one of the angles in the figure. This is usually found at the end of the exercises under "Application." This is NOT an application. I have ironed many shirts without ever knowing the angles of the legs. This was beautifully articulated at NCTM during Dan Meyer’s talk about real-world math. Students are brighter than this and they know it is not a genuine application. I think we lose credibility as professionals when we try to pass this over on them. In fact, I do not answer the question at all regarding "When will we ever use this?" Rather, I think it is the wrong question.

I often answer by asking students "why do we go to school" or "what is an education?" We discuss this a while, and then I show the mechanics of a common Pin Tumbler Lock and Key. A young child can open a lock with a key. An educated person, however, knows how the lock works, can take it apart, fix it, or can devise a better solution. Seeing a dynamic visual (try Youtube) draws students in and generates an "ah ha" result. It's a good example because the "how" is actually very interesting and you feel empowered to finally know what makes these locks work.

This approach is good for several reasons. First, it emphasizes that education is not merely practical (to learn a trade) but rather is the understanding and appreciation of the world in which we live. Second, it makes the point that education greatly adds to our life experience. Finally, it allows us to explain why we also study Shakespeare, the electromagnetic spectrum, painting, and a myriad of other ideas that add to our experience and growth.

An added benefit of this approach is the example of life-long learning. For instance, with the new knowledge of locks, we could now ask how a master key works to allow one person to open multiple locks while others can open only a single lock. We might ask how to pick a lock. Once we learn how to pick a lock, we would naturally think about how to make a lock that is more secure. Is fingerprint technology more or less secure? Retina scans? You may never "use" this particular knowledge of locks, but it is a springboard for inquisitive minds to ask more questions and pursue more knowledge. And, after all, knowledge is powerful and beautiful. Sometimes, though not always, it is even useful.